Tricolor. How Russia’s flag went from a patriotic banner to a symbol of war

Manage episode 457635313 series 3381925

At the end of 2024, fierce discussion flared up among the Russian anti-Kremlin opposition about the optics of bringing the Russian national flag to protest rallies. One side argued that the flag represents the Russian nation, which takes many forms beyond the current Putin regime; another said that Vladimir Putin and his government effectively own the symbol now. These days, the Russian flag means one thing to most of the world: political and military aggression and war. But in relatively recent history, its meaning has been quite different. Meduza takes a deep dive into the shifting significance of the Russian tricolor.

This essay is adapted from an issue of Signal, a Russian-language email newsletter from Meduza. If you enjoyed this piece, stay tuned. We’ve got a book coming in early 2025!

In November 2024, prominent members of the exiled Russian opposition held a rally in Berlin. Their aims were unclear, and the rally’s only tangible outcome was a sharp uptick in discussion about the significance of the Russian flag.

The majority of the flags at the rally were the Russian anti-war opposition flag, with a blue stripe between two white stripes, and the Ukrainian blue and yellow flag. Still, a few people arrived waving the Russian national flag, and their appearance sparked bitter debates at the rally. People called the flags “fascist tricolors,” “stinking bloody rags,” and the flag “of Putin and his ilk.”

Luka Andreyev, a 16-year-old who came to the demonstration carrying an official Russian flag, became the object of close (and often unflattering) scrutiny by journalists, and ended up on Myrotvorets, a Ukrainian website that lists individuals deemed Russian accomplices. But even relatively recently, the Russian tricolor was not as emotionally charged as it is today.

Even though we’re outlawed in Russia, we continue to deliver exclusive reporting and analysis from inside the country. Our journalists on the ground take risks to keep you informed about changes in Russia during its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Support Meduza’s work today.

A symbol of the state

The Russian flag is over 300 years old. Peter I designed its current form at the end of the 17th century, but the Tsardom of Moscow had been using the colors white, blue, and red as a state symbol since at least the 1660s. For a period in the second half of the 19th century, the white, blue, and red flag was in competition with a black, yellow, and white flag, which was designed in 1858 by the Russian imperial numismatist Bernhard Karl von Koehne. The tsarist government formally adopted the white, blue, and red banner as Russia’s national flag in 1898.

The Russian tricolor acquired its current emotional charge in the 1980s, when it became a symbol of popular protest against Soviet power. In Russia, as in a number of other parts of the collapsing USSR, supporters of regime change rallied around early-20th century national symbols, thereby emphasizing their wish to reinstate the normal course of national development that they believed the Bolsheviks interrupted. The Ukrainian, Belarusian, Latvian, and numerous other post-Soviet flags have essentially the same origin story.

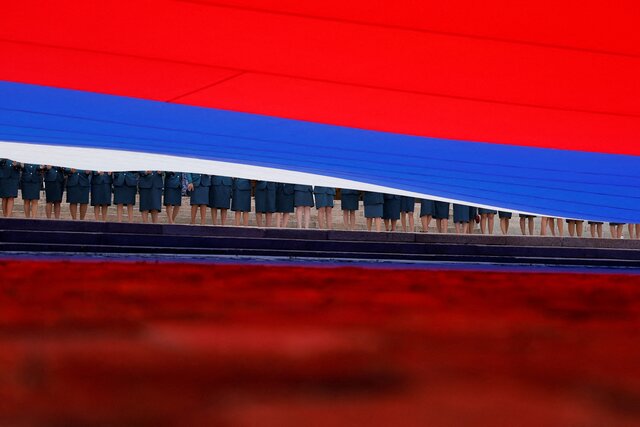

In August 1991, Boris Yeltsin made the tricolor Russia’s official state flag and on December 26, it replaced the red Soviet hammer and sickle above the Kremlin. The flag that flew in place of the Soviet flag in 1991 was actually different from the current Russian flag: its blue and red stripes were slightly different hues, and it had a different aspect ratio. The current flag was approved only in 1993, after the Supreme Soviet was officially disbanded and a new constitution was drafted. (The two flags are distinguished in Russia’s State Heraldic Register.) Some supporters of a democratic Russia say the 1991 version, not the one that patriots wave at pro-Putin rallies and occupying troops raise over bombed-out Ukrainian cities, is the “real” Russian flag.

That line of reasoning is unlikely to persuade critics, though — to most, the Russian tricolor is still the Russian tricolor even if some technical details differ.

The flag of democracy or a ‘fascist rag?’

At the end of the 1980s, when the tricolor became a meaningful political symbol, Soviet conservatives, who opposed policy changes under Mikhail Gorbachev, took to calling the flag the “Vlasov rag,” after Andrey Vlasov, a Soviet general who defected to Nazi Germany and nominally led the anti-Soviet Russian Liberation Army. The main argument in favor of the tricolor was basically the same as it is today: the flag has a long history, many important events have happened under it (including unsavory ones) but it is nonetheless a national symbol and its significance can’t be reduced to one historical episode.

Bringing a national flag to a protest is an important aspect of political speech all over the world. It shows that protesters maintain a feeling of national unity, however vociferously they may disagree with their current government. A national flag at a protest says that no one has a monopoly on patriotism — not even the state.

Until 2008, Russia had a paradoxical law in force prohibiting the free use of state symbols. But then, Russia’s soccer team beat the Netherlands in the European Cup quarterfinals, and thousands of people poured into the streets to celebrate. Many of them were waving Russian flags, and of course no one stopped them. Within a couple of months, the ban was lifted.

A year later, the opposition took advantage of this newfound freedom to celebrate Flag Day on August 22. It was a callback to a huge 1991 march, with 100,000 participants walking along Moscow’s New Arbat Avenue behind a huge tricolor banner that had become the emotional symbol of Yeltsin and the democratic reformer’s victory over the Soviet old guard. The liberal opposition turned out a far less massive and triumphant crowd in 2009. Nevertheless, in the years that followed, the Russian authorities would attempt to reclaim Flag Day, banning and dispersing any protests associated with it.

Russian tricolor flags were easy to spot during the widespread protests in Russia in the winter of 2011–2012. At that point, it seemed like Russia was on board with the standard practice: the authorities and the opposition could disagree as acrimoniously and confrontationally as possible, but they would do so under one national flag.

But then Vladimir Putin took over the presidency again, and domestic politics took a conservative turn. That was the beginning of the era of “traditional values” and state-sponsored patriotism. And the authorities wholly appropriated the tricolor at that point.

By 2014, the Russian tricolor flew over annexed Crimea, and the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics” used variations of the flag. Still, Russian flags flew, alongside Ukrainian ones, at protests against Russia’s aggression and occupation of Ukrainian territory. The consensus remained that the tricolor was a symbol of the Russian nation, not only of the Russian state.

Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine destroyed that consensus. The invasion started on February 24, 2022, and by February 28 the white-blue-white protest flag started to crop up more and more frequently. The most common version has different colors but the same aspect ratio as the 1991 tricolor.

It’s important that this protest flag appeared among émigré communities — and one of the reasons it quickly gained popularity in those circles is that people were simply embarrassed to protest under the flag of an aggressor country. Now, more than two years later, some activists interpret this as an admission of defeat, a surrender without a struggle. Opposition leaders, they say, didn’t even try to reclaim the national flag and instead simply “gave it away” to Putin.

The Russian flag and Russia’s war

Changes to political symbols often accompany regime change. The Bolsheviks swapped out the Russian tricolor for the red Soviet flag, and then when the Soviets lost power, Russia restored the tricolor. The Nazis traded the German tricolor for the swastika, and then when they were defeated, Germany reinstated its old flag.

Italy under Mussolini adopted a green, white, and red tricolor with the royal House of Savoy’s coat of arms in the center; after Mussolini’s overthrow, Italy ditched the coat of arms but kept the tricolor. After the Spanish Republic was proclaimed in 1931, the new government replaced the monarchic flag with a red, yellow, and purple one; then dictator Francisco Franco came to power and returned the monarchy’s red-yellow-red flag.

In Iran, following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the traditional green, white, and red striped flag lost its ancient emblem depicting a lion and the Sun, replacing it with a stylized inscription of “Allah,” and calligraphic renderings of the phrase “Allahu Akbar” along the edges of the green and red stripes. The old version of the flag (the “Shah’s” version) with the lion and sun remains a symbol of the Iranian opposition.

Something similar happened in Belarus. Immediately after Belarus declared independence from the Soviet Union, it adopted a red–white–red striped flag. Conservatives in Belarus, however, ceaselessly reminded their compatriots that Belarusian collaborators used this flag during World War II. The discussion was essentially a perfect analog for the one surrounding the so-called “Vlasov’s rag” in the Russian context, but it was resolved completely differently. In 1995, Aleksandr Lukashenko became the president of Belarus and held a referendum on national symbols, as a result of which the country’s first post-Soviet flag was replaced by what was essentially a remake of the Belarusian SSR’s flag (red with a green stripe on the bottom). Twenty-five years later, during the anti-government protests in 2020, the red–white–red flag became a definitive symbol of the Belarusian opposition.

It’s rare for completely new flags to be invented. Protests flags are usually old banners made new: they frequently symbolize a return to a “true path,” from which the opposition believes their country has deviated. The Russian tricolor in 1991, the Iranian “Shah’s” flag, and both post-Soviet Belarusian flags (depending on which path supporters consider to be “true”) fall into this category.

The opposition to the authorities in Russia during the early post-Soviet years attempted something similar. Under Tsar Alexander II, the Russian Empire’s state flag was a black, yellow, and white tricolor. Yeltsin appropriated the current white, blue, and red tricolor so successfully that his nationalist-minded opponents brought the imperial flag back as an anti-government symbol. (For some reason, they flipped it upside down, so that the white stripe was on top and the black on one the bottom.)

Like the Iranian lion and sun flag and the Belarusian red and white banner, the Russian imperial flag represented an appeal to national history, but it was a history that was already long since forgotten, and that flag never functioned well as a unifying symbol. For a period, it was the flag of avowed nationalists. There was an attempt to make it the flag of Novorossiya, as Russian nationalists call some of the occupied regions of Southern Ukraine, but Novorossiya has yet to come into existence. At this point, almost all Russian nationalists have become Putin loyalists and adopted the official tricolor. A small number are fighting for Ukraine with the Freedom of Russia Legion under the white and blue protest flag.

More on Russia’s pro-Ukraine fighters

Today, Putin and his government “own” the Russian tricolor. Of course, arguments about flags aren’t really about the flags. Rather, they’re an expression of frustration: the Russian opposition is fractured and powerless, and its members know this. The lack of a unifying symbol is only a symptom of the lack of unity as such, an absent sense that a diverse group of people might work together for a common cause.

After February 24, 2022, the Russian flag acquired one very specific meaning everywhere in the world. If you see someone on social media using the Russian tricolor in their avatar or user picture, you can make a very decent guess as to how they feel about the war and the Putin regime. This overrides any other feeling you may have about the flag.

Any attempts to give the Russian tricolor a new meaning (or to return its old democratic significance) run up against strong resistance that few in the Russian opposition, especially people in emigration, are prepared to overcome. It’s easier to find a new symbol than to have to prove that the flag is Russian, and not Putin’s. Hence, the blue–white–blue flag.

The problem is that new symbols immediately take on extra, unintended significance. The anti-Putin opposition uses the same blue and white flag as the Freedom of Russia Legion, a relatively fringe nationalist group. This is always the way: any symbol that claims to represent an entire nation will eventually come to represent people that you, personally, don’t like. That’s what happened with the Russian tricolor, too.

The issue isn’t really with the symbol itself, but rather with who has the will to defend the meaning with which the symbol is invested.

Read more about the anti-war flag

68 tập