The Life of a 17,000-Year-Old Infant from Ice Age Italy

Manage episode 455820075 series 3444207

In a remarkable feat of ancient DNA analysis, researchers have reconstructed the genetic story of a baby boy who lived over 17,000 years ago in Ice Age Europe. The findings, published in Nature Communications1, reveal a wealth of information about the boy's ancestry, physical traits, health, and the environment in which he lived, offering a rare glimpse into the lives of prehistoric humans.

The boy’s remains, discovered in 1998 in Grotta delle Mura, a cave near Monopoli in southern Italy, were uncovered during archaeological excavations. Carefully laid under slabs of rock without grave goods, the burial stood as the cave's sole interment, raising questions about the significance of his death in a small, tight-knit community.

Unlocking the Boy’s Genome

A team of international scientists, led by Alessandra Modi of the University of Florence and Owen Alexander Higgins of the University of Bologna, analyzed 75% of the infant’s genome, which was unusually well-preserved due to the cool, protective environment of the cave. The genetic material allowed researchers to reconstruct details about his physical appearance, ancestry, and even the health challenges he faced.

Physical Traits and Ancestry

The genetic analysis revealed that the boy likely had dark, curly hair, blue eyes, and skin pigmentation darker than most modern Europeans but lighter than populations living in tropical climates. He belonged to an ancestral group tied to the Villabruna cluster, a population that emerged in southern Europe around 14,000 years ago. This connection pushes the timeline of the Villabruna lineage further back, suggesting that this group may have originated in southern Europe well before the end of the Last Glacial Maximum.

“This study represents a significant step forward in understanding the ancestry of post-Ice Age populations in Europe,” said Higgins. “The infant’s genome ties him to a lineage pivotal to understanding human migration and adaptation during this period.”

Insights into Health and Life Circumstances

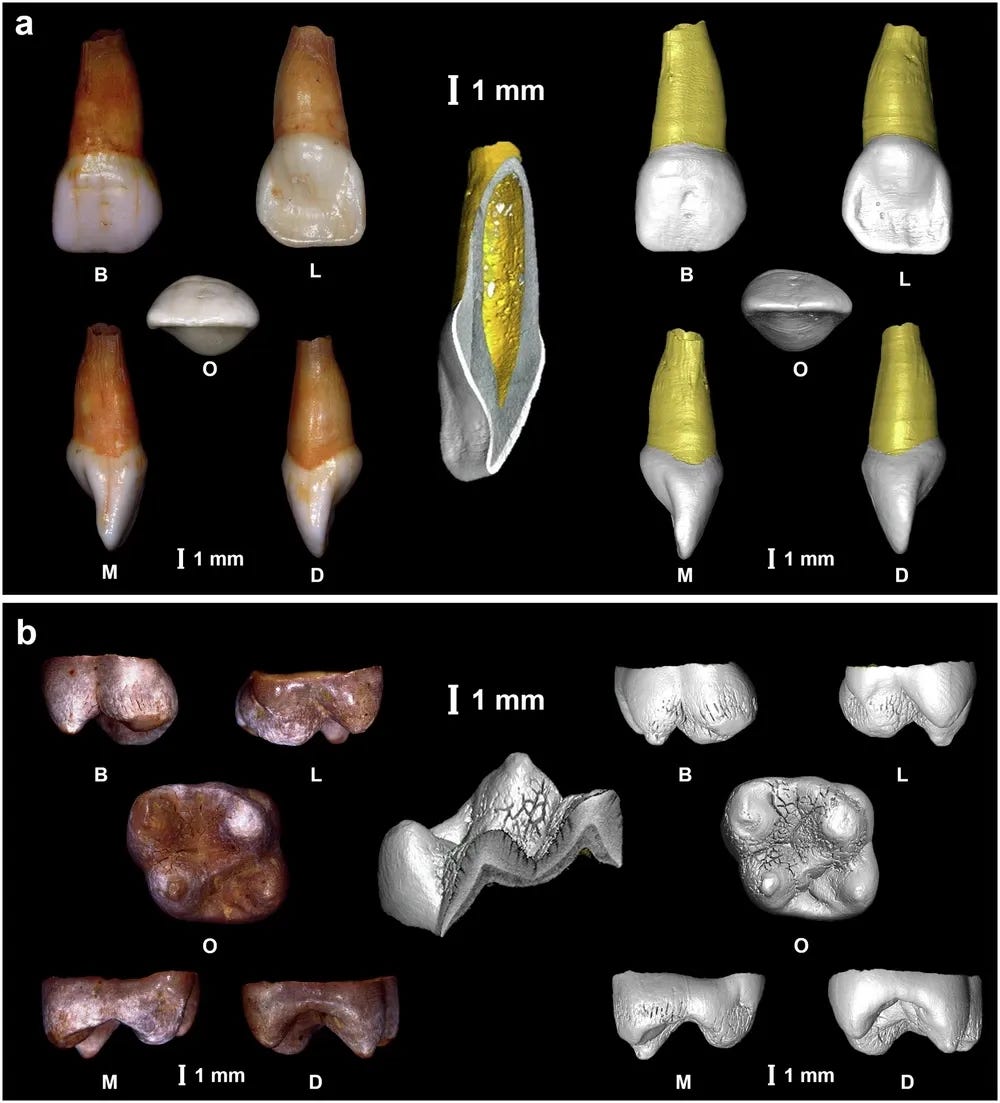

Beyond ancestry, the boy’s remains revealed poignant details about his short life. The infant suffered from familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a genetic condition that thickens the heart muscle and can cause sudden death. This condition likely contributed to his premature passing. Additionally, isotopic analysis of his teeth uncovered signs of physiological stress during infancy, possibly linked to malnutrition or hardships faced by his mother during pregnancy.

Researchers also observed wear patterns on the baby’s teeth that hinted at a diet consisting primarily of plant-based foods. Combined with evidence of limited mobility during his mother's pregnancy, the findings suggest a localized lifestyle centered around resource gathering in a specific region.

A Challenging Birth and Early Community

The infant’s fractured collarbone provided evidence of a difficult birth, possibly indicating complications that may have impacted both the child and his mother.

“We imagine his mother as part of a small, close-knit group, deeply connected to their local environment,” said Higgins.

This community likely relied on gathering, hunting, and resource sharing to navigate the challenges of Ice Age Europe.

Burial and Significance

The burial itself was stark yet carefully executed, with slabs of stone placed over the body. Unlike more elaborate funerary practices found elsewhere during this period, the simplicity of this interment raises intriguing questions about social structures, spiritual beliefs, and resource constraints in his community.

Broader Implications for Ice Age Research

The study builds on a growing body of research into the genetic and cultural diversity of Ice Age populations. Vanessa Villalba-Mouco, a paleogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, who was not involved in the study, remarked, “This work provides an invaluable piece of the puzzle in understanding human adaptations and migrations during the Last Glacial Maximum.”

Future Directions in Ancient DNA Research

The findings pave the way for further investigations into early European populations. Researchers hope to apply advanced genetic techniques to additional Ice Age remains, illuminating how prehistoric humans adapted to extreme environments and how these adaptations continue to influence modern populations.

Additional Related Research

Pinhasi, R., et al. (2015). "Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia."

Nature, 514(7523), 445-449.

DOI: 10.1038/nature13810This study provides insights into early modern human migrations and interbreeding with Neanderthals.

Villalba-Mouco, V., et al. (2021). "Survival and adaptation of humans during the Last Glacial Maximum in Iberia."

Current Biology, 31(5), 1110-1120.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.11.029Focuses on human resilience and adaptations in Ice Age Iberia.

Mathieson, I., et al. (2018). "The genomic history of southeastern Europe."

Nature, 555(7695), 197-203.

DOI: 10.1038/nature25778Discusses genetic continuity and population changes during the transition from the Ice Age to early agriculture.

Higgins, O. A., Modi, A., Cannariato, C., Diroma, M. A., Lugli, F., Ricci, S., Zaro, V., Vai, S., Vazzana, A., Romandini, M., Yu, H., Boschin, F., Magnone, L., Rossini, M., Di Domenico, G., Baruffaldi, F., Oxilia, G., Bortolini, E., Dellù, E., … Caramelli, D. (2024). Life history and ancestry of the late Upper Palaeolithic infant from Grotta delle Mura, Italy. Nature Communications, 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51150-x

5 tập